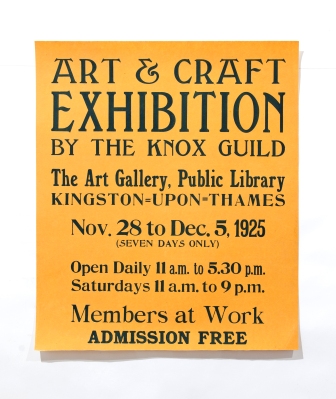

In February, Heritage Supervisor Carolynne Cotton got in touch to let me know that the Legal Department at Kingston Council had given Kingston History Centre a set of illuminated addresses. Carolynne thought these might be connected with the Knox Guild and spotted the telltale initials ‘DKT’ for Denise Kate Tuckfield (later Denise Wren). In April I went to take a look to see whether I could identify any more of the artists from the initials on each of the addresses. Kingston Heritage Service kindly allowed me to include the images I took of the addresses here.

These beautiful documents were created in ink on vellum and were made to record addresses written to thank to individuals who had rendered services to Kingston Borough or to welcome elite visitors on ceremonial occasions. In my last blog post, I speculated that Town Clerk Harold Winser, himself a member of the Knox Guild, may have got to know the group through commissioning exactly these items from them. I already knew of one illuminated address created by Denise Tuckfield for Robert Baden Powell in 1913.

This newly discovered set of illuminated addresses date from the decade 1899 to 1909 and I was initially very excited to see the initials ‘DKT’ and ‘WT’ on some of them, which I assumed were respectively ‘Denise Kate Tuckfield’ and ‘Winifred Tuckfield’. However, Denise (b.1891) and Winifred Tuckfield (b.1889) would each only have been aged ten when the earliest of the addresses is signed with their initials, respectively in 1901 and 1899. It is difficult to believe that a ten year old would be capable of such fine work. And it seems that these are original documents, since they are held by Kingston Council. Nevertheless, I wanted to feature them in a blog post as they are so interesting and may have a connection with Kingston School of Art.

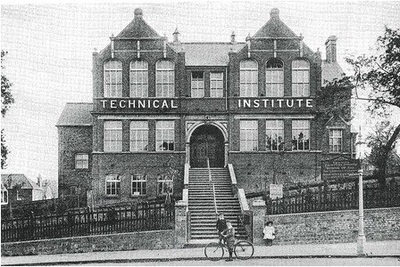

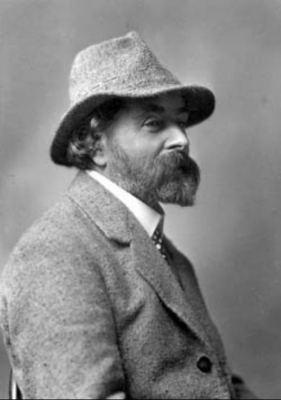

Carolynne speculated that perhaps Kingston Council commissioned the addresses through Archibald Knox. I think this is very likely, as Knox became Design Master at the Art School from 1897 and the first address dates from 1899. During classes, Knox got his students to copy the vivid symbols and colours of heraldic devices. He used these as examples to show the students how to build up designs. The Wren Archive held by Kingston Heritage Service has many drawn and painted crests and shields which Denise Tuckfield created during her art school course. One of the few published texts by Knox evidences his interest in this topic. Entitled ‘The Arms of the Earl of Surrey’, it appeared in 1907 in The Well, the Wimbledon School of Art magazine. (1)

Knox also had a longstanding interest in calligraphy and interlaced patterns, inspired by his passion for Celtic design. He travelled to Dublin to see the best examples of Celtic art, such as the illuminated manuscripts of the Book of Kells. Knox developed his own calligraphic alphabet, in which the letter forms were based on a circle, which Denise copied as an exercise. Rosemary Wren, Denise’s daughter, recalls Knox travelling from the Isle of Man to the Oxshott Pottery when she was a child in around 1930. There, he led a workshop for Knox Guild members on lettering and drawing. (2)

Knox went on to produce many works of calligraphy, including an ‘illuminated manuscript of an early Irish hymn traditionally attributed to St. Patrick, The Deer’s Cry made during the First World War. Afterwards, he created ‘another illuminated book commemorating the staff and students of Douglas High School who served in the First World War’, his own former school on the Isle of Man. (3)

As all of the illuminated addresses shown here are a combination of calligraphy, heraldic devices and interlacing, it seems most probable that Knox had some hand in them. However, there is no mention of Denise and Winifred Tuckfield having contact with Knox before they started their art school course. So, were the Tuckfield sisters precociously talented? Or were they copying designs suggested by Knox? Or are the initials misleading? Perhaps answers will come to light at a later date. What follows are details of each of the addresses in chronological order.

The Right Honourable William Court Gully, QC, MP, The Speaker of the House of Commons

26 October 1899

Signed ‘WT’, presumably for Winifred Tuckfield. The front shows a striking design of a hand holding a winged sword and the inside is decorated with stylised flowers.

This address was presented on the occasion of the unveiling of a stained glass window in the Town Hall, paid for by public subscription. It commemorated ‘the granting, about seven centuries ago of the first recorded charter of the liberties of this borough, the grantor being that king from whom a few years later was obtained that great historic charter of our nation’s liberties.’ This is a reference to the Magna Carta of King John, who also granted Kingston’s first charter in 1200. The address points out that 1899 also marks one thousand years since the death of Anglo Saxon King Alfred and the coronation of his son King Edward the Elder. The window was later moved to Kingston Museum where it can still be seen.

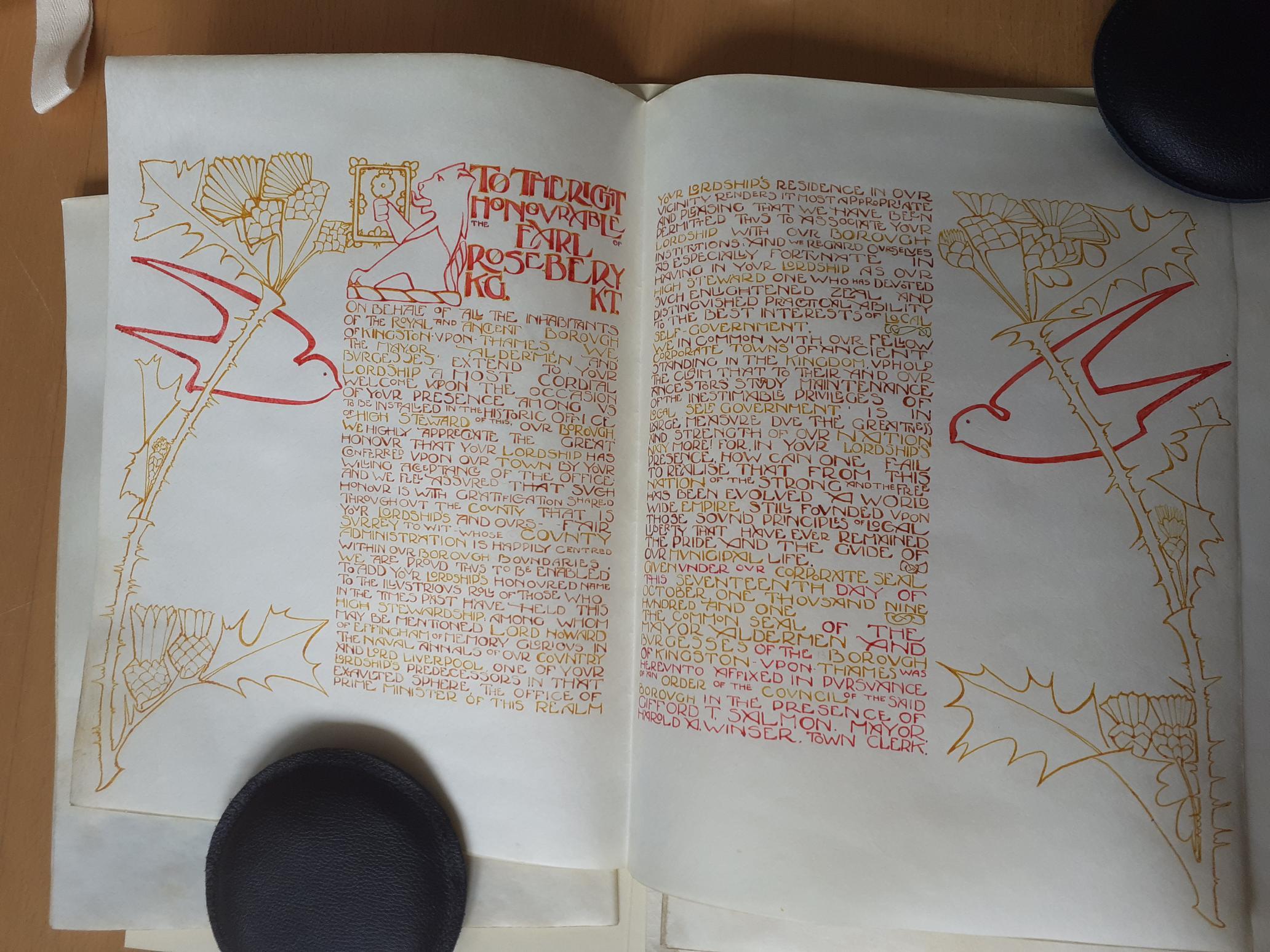

The Right Honourable The Earl of Rosebery, KG, KT

17 October 1901

Signed ‘DKT’, presumably for Denise Kate Tuckfield. A magnificent depiction of the coat of arms of the Earl of Rosebery with white lions rampant holding a shield with black lions upon it and the motto ‘Fide et Fiducia’ : ‘In faith and trust’. The lettering closely resembles Knox’s calligraphic alphabet and this design, as well as the one inside, is stylistically very similar to Denise Wren’s later work. Inside, the text is written between two thistles with birds on the wing, forming an unusual and sophisticated design. The thistles are a reminder that the Earl’s title is part of the Peerage of Scotland.

The address was given on the occasion of the Earl of Rosebery’s installation in the historic office of High Steward of the Borough. In October 1904, the Earl officially opened Kingston Museum, venue for many Knox Guild exhibitions.

The Right Reverend Edward Stuart Talbot, D.D., The Lord Bishop of Rochester

17 May, 1902

Signed ‘GB’. The sole member of the Knox Guild with these initials is Annie Begg’s sister, whose first name is not known. Only her initials appear in the Knox Guild catalogues of their three exhibitions at the Whitechapel Gallery in the 1920s, where she is listed as a ‘Guild Raffia Worker’. But the document could equally have been created by an art school student with these same initials. Geometric flowers and foliage surround the calligraphy.

The address commemorates the Bishop of Rochester’s visit to Kingston to unveil the ‘millenary memorial window’ celebrating the occasion of the crowning of the Anglo Saxon King Edward the Elder in Kingston one thousand years previously. This stained glass window was designed by Dr. Finny, seven times Mayor of Kingston. Like the window commemorating Kingston’s first charter, it is now incorporated into Kingston Museum. The address notes that Talbot is the hundredth bishop to hold this post. He went on to become Bishop of Southwark, then Winchester.

His Excellency the Japanese Minister Viscount Hayashi

April 23, 1902

Signed ‘MC’. It is likely that this was Marian Coombes who also made a number of lithographs depicting the local area. She later joined the Knox Guild and there are more details on her in the post about them below. On the front of the document are birds perched on the cross of St. George and inside are birds flying. This stylisation of avian forms was termed ‘Knoxical’ by Denise Wren, as it was adopted from Knox’s way of depicting birds. Denise often used similar shapes, for example on publicity for Knox Guild exhibitions held at Kingston Museum and the Whitechapel Gallery.

This address was made for the visit of Viscount Hayashi to unveil the renovated statue of Queen Anne on the bicentenary of her coronation. Her gilded likeness still looks down on Kingston Marketplace from the centrally located Market House. Hayashi is named inside as the representative of the Emperor of Japan. In 1902 Britain and Japan signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance as a defence against Russia expanding its influence within Asia. The address references ‘that great nation with whom ours has entered into such friendly relations’. It also cites the fact that Viscount Hayashi had chosen Kingston Borough for his summer residence for the previous two years.

His Serene Highness Prince Alexander of Teck and Princess Alice of Albany

6 February, 1904

Signed ‘DKT’. It is more feasible that Denise Wren could have made this design aged thirteen, and would explain the spelling error in the word ‘approching’. Knox’s favourite decoration, intricate interlacing like that found in Celtic illuminations, is much in evidence here. Denise’s art school work shows that she was a talented draftswoman, who once acknowledged that she was ‘born being able to draw’. (4)

Princess Alice was the last surviving grandchild of Queen Victoria and Alexander of Teck was her second cousin once removed, both being descended from King George III. The address wishes them a happy marriage, explaining that ‘As our borough is near to and mid way between the residences in which (you) respectively passed your earlier lives, the announcement of your marriage has elicited peculiar interest and pleasure amongst us…’ Its further declaration that ‘It is our fervent hope that by the blessings of Providence you may long be spared to enjoy health, happiness and mutual love’ was granted, with Alexander living until the age of 83 and Alice surviving to 98.

Bedford Marsh Esquire, Ex Alderman of the Borough of Kingston upon Thames and Justice of the Peace for the Borough

20 December 1904

Signed WT for ‘Winifred Tuckfield’. Winifred had early experience of making technical drawings to accompany the patent applications made by her father, Charles Tuckfield, an inventor. During the First World War she worked as a draftswoman at the National Physical Laboratory. This talent would have helped her to plot the intricacies of the interlacing in the centre of this address, which is laid out like the page of an illuminated book. The text celebrates the occasion of Bedford Marsh’s ‘well-earned retirement after…nearly forty years’.

Alderman John James Collings Esquire JP

25 September, 1906

Signed ‘MEC’, presumably not Marian Coombes, this does not match any other initials of a Knox Guild Member. Art Nouveau style flowers embellish the front and inside of the document. The address congratulates Alderman Collings on his marriage, which must have been made in later life, as he had already been a member of the Council for over 28 years.

Magnus George Moatt Esquire, JP

28 September 1909

Signed ‘MEC’. One word has been inserted after it was missed out and the names of Mayor Finny and Harold Winser are pencilled in, rather than inked, giving this document a slightly unfinished feel. The address was presented on Moatt’s resignation of the office of Alderman of the borough and highlights ‘Your indomitable and successful efforts for the provision of efficient bands of music in our beautiful public gardens whereby nature and art happily conduce to the refined enjoyment of the inhabitants’.

William Garn Esquire, Ex-Alderman of the Borough

9 November 1906

Signed ‘GB’. The inside has a lovely rendering in blue and green ink of the three salmon from the arms of Kingston Borough. Very similar fish feature in some of Denise Wren’s later designs. The address commemorated Garn’s retirement from the Council after a twenty year membership.

Images Courtesy of Kingston Heritage Service

References

(1) Wren. R (2001) ‘New Light from Old Records: Archibald Knox’s Approach to his Work’ in Martin, S. Archibald Knox London: Art Books International, p.110

(2) Wren. R. (1997) The Knox Guild and Its Background: A Scrapbook of Recollections and Pictures with an Archival Index unpublished folder deposited in several archives including Kingston Heritage Service, p.15-16

(3) Anscombe, I. (2001) ‘A Sense of Place: Knox, Manx Nationalism and the Celtic Revival’, in Martin, S. Archibald Knox London: Art Books International, p.101

(4) Wren. R. (1997) The Knox Guild and Its Background: A Scrapbook of Recollections and Pictures with an Archival Index unpublished folder deposited in several archives including Kingston Heritage Service, p.10